mongoodtimes.jpg

“Photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing and when they have vanished there is no contrivance on earth which can make them come back again.” Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004)

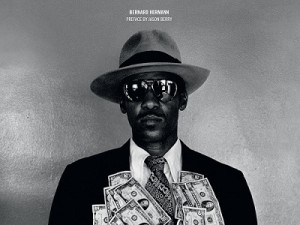

Bernard Hermann’s “The Good Times Rolled: Black New Orleans, 1979-1982” is a long-lost valentine delivered in black and white. A native of France, Hermann had been traveling the world photographing its great cities, spending a few months in each. But when setting out to do similar work in New Orleans he found a city “that offered [him] four years of passionate life in her perennial party girl’s embrace…where [he] was spellbound, entranced, zombified, by some mysterious spell.” Like many seasoned travelers, Hermann compared New Orleans to exotic Caribbean locales: “[It] felt more like Haiti, Cuba or Jamaica than the United States. Everybody knew everybody, called out to one another, kept an eye on what went on…watching the neighborhood soap opera unfold….”

Hermann begins his book with richly contrasted photos of people as they go about their day: men toiling on the docks along the Mississippi River; women in roller sets; children at play; a barber waiting for customers; sports in elegant finery posing languidly on luxury cars. A scene of a second line breaking up hints at what is to come, because ultimately, this is a book about street culture. This was a very important time period in the evolution of second line and Indian culture as we experience it today. The folks Hermann captured on film enjoyed that gap between a rather staid style of musicianship while fueling the “do whatcha wanna” ethos that was shaped by the Olympia, Chosen Few and Dirty Dozen Brass Bands: “Bourbon Street Parade” had been replaced by “Night Train.” The book’s cover, a portrait of a young Benny Jones on his birthday, is especially apropos. As one of the founders of the Dirty Dozen, he is a godfather in the modern street scene.

The book continues with fantastic pictures of the Money Wasters, Scene Boosters, and Gentlemen of Leisure Social Aid & Pleasure Clubs in their prime, and those with a discerning eye will spot a younger “Uncle” Lionel Batiste in several of these shots. We see “Big” Al Carson, the Bourbon Street blues belter who is largely forgotten for his parade-walking, sousaphone-playing days. It is comforting to see another modern street godfather, Anthony “Tuba Fats” Lacen, in fine form.

Before returning to the streets, Hermann shifts his focus to New Orleans’ unique spiritual churches and their “Sunday’s laundry of souls.” Here, a white Jesus is as present as the spirit of Black Hawk. Hermann explains, “In South Louisiana … a local Afro-Caribbean syncretism survived,” a phenomenon that was often misinterpreted by “Protestant rednecks who saw the Devil’s voodoo everywhere there were blacks.”

Hermann also visited upon New Orleans’ death rituals. His “final photographs” of deceased citizens in their caskets recall the work of Harlem Renaissance portraitist James Van Der Zee. Note that several of these shots were taken at a fully operational Blandin Funeral Home, now the site of the Backstreet Cultural Museum. In his photos of jazz funerals, we see musicians in then-customary “black and whites,” and also the timeless attire of Grand Marshals, in their pork pie hats and sashes, doves perched on their shoulders.

Back in the streets, Hermann tried to run with the Mardi Gras Indian gangs but “the first time [he] tried to photograph a group [he] was hit with a lance or a tomahawk” and after trying to sneak into one of their bars was “roughly evicted and faced serious threats.” Fortunately Hermann learned to “’play Indian’ according to their rules” with guidance from members of the White Eagles and others in the community. That hard-earned counsel resulted in some of the very first intimate photos of Big Chiefs, Wild Men, Spy Boys, and Queens ever taken by a white man.

Hermann was also one of the very few photographers allowed access to Angola State Penitentiary, and he chose to end his book with grim photos of inmates doing their time. Gangs of men working under the watch of armed guards are presented alongside dejected men languishing in single cells, 23 hours at a time. Comparatively bright moments include the annual prison rodeo, or a simple game of chess played between locked cages. “Angola stank of death,” Hermann laments. “After each visit I felt such blues…”

Hermann’s photography walks a fine line between the documentary style of Jacob Riis, who used the form as social commentary, and the street style developed by fellow countryman Henri Cartier-Bresson, who championed “the decisive moment” that makes for compelling pictures. Working in an era when a keen eye, sharply-honed technical skills and split-second timing were required to capture iconic images, old-school photographers remained uncertain of success until they emerged from the dark room (yes, a dark room).

Today’s digital photography leaps out from the page with vivid color in sharp definition. These photos draw one deeply into an earthy realm: You can smell the marijuana (“Between alcohol and drugs,” Hermann observed, “hardly a single Pilgrim was chemically neutral.”). You can hear the drums. You can feel the heat rise up from the asphalt.

Hermann’s photographs possess an insider’s view thanks in part to native New Orleanian photography duo Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick. At the time he took these pictures, Hermann asserted that he “inhabited neighborhoods where no tourists ventured.” That seems almost unimaginable in modern New Orleans where no indigenous ritual or space is safe from exploitation.

As Hermann packed for his return to Europe, he listened to a new community radio station, WWOZ. He left New Orleans and never came back. In the book’s epilogue, Hermann discusses the world’s perception of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. “It was almost inconceivable that the world’s greatest superpower could not or would not help its most vulnerable citizens on its own soil during a natural disaster.” New Orleanians still parade and dance and laugh, work, cry and die in the very streets Hermann photographed. What he could not know was that much of what he knew was already long gone. Thankfully, we now have this splendid artifact of those special times.

"The Good Times Rolled" is available for purchase from all of the finer bookstores in your area, or online from Amazon.